(Contributed to Sikh Council UK draft message)

2011 has been one of the most eventful years in recent history. The world population now exceeds 7 billion. We face global economic crisis while natural and man-made disasters have taken their toll. Tyrannical regimes have tumbled and the most wanted terrorist in the world, Osama bin Laden, has been killed.

We watched helplessly, as the summer madness swept across English cities and shops and businesses were looted and set on fire.

The Sikh Council UK agrees with the Prime Minister David Cameron when he warned us following the summer riots, that these unprecedented events were “a wake up call for the country.” Indeed, it was also a wake up call for all religious communities in the UK to work together to meet the challenges of diversity in human society, and to unite by sharing human values preached by all religions..

The economic and environmental challenges which the ever shrinking global village continues to face, seem almost unsurmountable. Yet these challenges can also be a spur to finding solutions for the survival of the humankind.

Sikh thought stresses, “Where God exists there is no selfishness, where self exists there is no God.” There is need for balance between material ambition and spiritual well-being. Community involvement is necessary for the creation of a just and peaceful society. Every person needs to work for peace; especially those who lead communities, and those who are in positions of power and authority.

To the religious zealot, the Sikh message is clear: God is everywhere and in everyone; no religion is superior to another. No matter which religious path one follows, all will miss their final religious objective without truthful conduct and good deeds. There is no place for terrorism in true religion; nor for those who incite hatred against other religions.

It is futile to seek converts to own religion by condemning others and fighting wars in the name of religion. True religion should seek converts to peace and contentment while respecting the rights of others.

In connection with religious freedom, Britain has led the world in respecting the rights of people from many diverse religious backgrounds. Sikhs are proud of their “British” identity. Sikhs are also proud of their distinct Sikh identity which is associated with their outstanding military service in Europe during the two World Wars.

The Sikh Council UK looks forward to working with the British government in 2012, to persuade EU countries to fully accept Sikh identity as an important religious right.

Today we see the results of selfish pursuit of power and wealth, and irresponsible consumerism. There is much human poverty and suffering while the rich get richer. Guru Nanak’s universal message to humankind is highly relevant: to live a life of service, a life of sharing with others, and belief in equality of humankind before One Creator of all.

Sikhs invite people of all beliefs to do something about the environment to save “Great Mother Earth” (Mata Dharat Mahat).

How the human race rises to the challenges ahead, will shape the world in the years to come.

Gurmukh Singh

E-mail sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

© Copyright Gurmukh Singh

Articles may be published with acknowledgement

Sunday, 25 December 2011

Friday, 23 December 2011

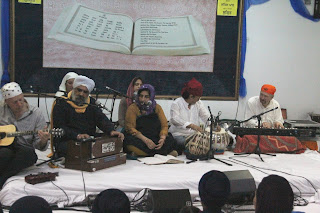

Dya Singh of Australia at Jalandhar, Punjab.

Flanked by a “taoos” playing maestro on one side, and a Guiness record holder, tabla player, on the other, it was an unlikely setting at Jalandhar in central Punjab, for world renowned Dya Singh of Australia. For the first time, he was finding himself at a Kirtan smagam, without his motley group of musicians playing a range of East-West musical instrumental blends.

He enthralled the Sangat at this private programme on 1 November, 2011, with classical reets (tunes) reminiscent of great classical ragis like late Bhai Avatar Singh.

Dya Singh had stopped at Delhi for a couple of days on his way to the family home at Ludhiana in Punjab. He was invited by a jatha of Gursikh shardhalus (devotees) to join them on their monthly trip for Sangrand darshan of Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple, Amritsar) on specially booked coaches on the Shtabdi train. The condition for this free ride was simple. “Please do Kirtan taking your turn with other raagi jathas while travelling with us”, That was the request of the organiser. Dya Singh’s host at Delhi agreed readily before he could say a word!

And so it was “Charan chalo marag Gobind.” (With your feet walk the Lord’s path) sung by the whole jatha in three coaches linked by CCTV system. The waves of the divine Sangat Kirtan led by Dya Singh, floated across the farmlands of Haryana and Panjab as the train covered miles of countryside. However, before he reached Ludhiana he had been “persuaded” (Khalsa style) to do a special Kirtan programme for Kirtan devotees at Jalandhar.

He was alone during this Punjab trip, and, so far he is concerned, a stranger in his own country of origin. (He was born in Malaysia.)

And so, Paramjot Singh, who rose to fame by getting his name into the Guiness Book of records for playing tabla continuously for 113 hours, 13 minutes and 13 seconds, and musical teacher specialising in taoos, Sri Pal Singh, came to the rescue. I had covered Paramjot’s record breaking tabla playing story in my UK columns and he is a regular visitor at home in Ludhiana.

Dya Singh mentioned in the introduction, that the “taoos” played by Sri Pal Singh, is a string instrument (like Indian sarangi, only deeper and more melodious), which was made popular by Guru Hargobind Sahib.

So, on 1st November, 2011, the trio found themselves together at Jalandhar Kirtan society’s programme. The deep sound of the taoos filled the environment as the mixed Sangat (Sikhs and, apparently, non-Sikhs) – all Kirtan lovers – listened in deep meditation. Dya Singh’s heart-piercing rendition of Shabad refrain, “Hao reh na saka(n) bin dekhay mery maaee” (I cannot live without the holy sight of my Beloved, O my mother) touched all hearts. I was particularly moved by the classical notes of the taoos and Sri Pal Singh’s soft vocal accompaniment.

Madhwanti Kalyan captured the evening mood. A Shabad, Eh doay naina matt shoho Pir dekhan ki aas” (Touch not these two eyes (a plea to the crows) for I still have hope to see my Beloved Lord) by Bhagat Farid, was a request from an elderly Sikh who came up to the stage.

Paramjot Singh accompanied with sympathetic taal (beat) variety, enhancing the Shabad impact, and excelled in controlled tabla display. During such displays, he alternated effortlessly between deep sounding “mardang” type of beat from a wide-top tabla, and ordinary “kinaar”.

Fortunately the sound quality of the, otherwise amateurish video of this private Kirtan programme, is good. With professional editing this can be Dya Singh’s first successful Kirtan video. I have watched this programme several times on video and wonder, if Dya Singh, an accountant by training, could not have done better by becoming a traditional Kirtania.But then, who else could have taken the universal Message of Sarab Sanjhi Bani to mixed global audiences in Dya Singh’s unique pioneering Sikh world-music style?

Gurmukh Singh UK

E-mail: sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright: Gurmukh Singh

This article may be published with acknowledgement.

Thursday, 15 December 2011

Sikh Council UK & Sikh Issues

Background:

Due to the longstanding need felt by British Sikhs, the setting up of the Sikh Council UK has been widely welcomed. The Council has gained rapid recognition in government circles and is settling down to address the most important challenges we face today.

This is perhaps the right time to remind ourselves what the main issues and challenges are.

Internal divisions centred around personalities have been a major setback for Sikh unity and progress of Sikh issues. Effective communication at local and national levels in English has been the other difficulty. Without balanced presentation of Sikh problems to the government and departments in the language of the British establishment, Sikh jathebandis are unable to influence government policy.

In the past, some ambitious individuals have used the language difficulty to pursue own agendas. The influence they have on Sikh affairs has been far in excess of their knowledge of Sikh tradition or actual support at grassroots level. For example, the French Sikh turban case could have been handled much more openly and effectively from the start. However, personal ambition rather than knowledge of Sikh religious significance of dastaar, took over. In an attempt to seek exemption from French restrictions, by some clever argument, Sikh dastaar was presented as a “cultural” item instead of an essential religious requirement. Regrettably, as in other such cases, history is being re-written to gloss over such errors. In this case, other organisations were blamed for Sikh failure.

Despite some achievements, UK and European acceptance of Sikh identity has been incremental, and grudgingly conceded after much lobbying, demonstrations and legal battles. Due to lack of co-ordinated professional team-working at frontline level, progress made on the most important issues has been limited.

At individual level Sikhs are prosperous. Next generations are doing well in education and professions. However, despite being a sizeable community, Sikh identity is hardly seen in public life, politics and the Parliament. There is much ignorance about who Sikhs are. Future Sikh generations need to be proud of the “Sikh” part of their “Sikh British” identity to grow up as responsible citizens fully aware of own heritage and culture. Sense of belonging to a community is an important aspect of personal development and identity.

That sense of pride and belonging also depends on the acceptance of the community’s identity within the larger British plural society. That is one important goal for the Sikh Council UK.

Past achievements: Setting the record straight

Those who claim that they have been able to get results only through personal contacts are out of touch with ground realities. Despite exaggerated claims of individual contribution, success in the Mandla case, for example, was due to united support by the Sangat. The case reached the House of Lords and is regarded as a milestone achievement.

To set the record straight, I am content to quote S. Sewa Singh Mandla. In response to a query to clarify how the case was won, he wrote on 17 May 2010:

“A couple of years ago the Sikh Police Association London at their AGM wanted to celebrate 25th anniversary of Mandla v Lee case and had invited me to give a talk on the case and make a presentation, which I did. In my talk I said that having lost the case in the lower courts I realized that this case will affect the entire Sikh Community and as such I wanted to involve the Community in the case. With this in mind I went to Sant Baba Puran Singh Ji the Founder of Nishkam Sewak Jatha Birmingham (GNNSJ) and sought His Blessing and assistance.

It was GNNSJ who prepared information packs about Sikhism and the importance of the Turban to the Sikhs and send them out to all Members of Parliament and other important people to increase awareness and support. GNNSJ got support from all communities for this cause. It was GNNSJ which took a lead in the campaign and organized a mass rally at e Hyde Park in London . I showed the clip of the BBC Television interview with Sant Baba Puran Singh Ji, Bhai Sahib Norang Singh ji (the then Chairman of GNNSJ), Mr. Mavi of (CRE) and my self and I finally said that the case in the House of Lords was won purely with the Blessings of Sant Baba Puran Singh Ji. Now that is the truth. I know that it was GNNSJ who mobilised the entire community and in fact hired 70 coaches and send them to the Gurudwaras and other organisations who wanted to attend the rally at the Hyde Park.” (S. Sewa Singh Mandla’s e-mail of 17 May 2010)

Yet, this collective historic achievement is being re-written with a bias towards individual contribution to the ultimate success. The opportunity to build on a milestone victory for Sikh unity and identity, has been lost

The historical fact is that past achievements were due to united effort by Sikh Sangats. There are important lessons to be learnt. Ambitious activists with language and communication skills, otherwise dedicated to Panthic work, tend to take personal credit far in excess of their actual contribution. Their proximity with departmental officials gives them own following in the community. That is not in the community’s long term interest. Individuals with language skills should serve jathebandis; it is not for jathebandis to serve their personal aspirations.

Issues for the Sikh Council UK

The establishment of the Sikh Council UK gives us an opportunity to review the most important issues which concern us as a distinct religio-social community; the extent to which progress has been made and the challenges which we continue to face. These would be matters which need to be taken up by the Sikh Council and affiliated organisations, with the UK and European governments, agencies and authorities. Most other issues can be dealt with by Sikh organisations and Panthic jathebandis with experience in specific areas. Anglo-Sikh heritage, Khalsa Aid and legal representation of Sikh issues e.g. by United Sikhs, are important activities which promote Sikh identity, but need not be dealt with in the context of matters discussed under the umbrella of Sikh Council UK.

With regard to Sikh expectations from the British establishment (mainly the legislative/legal and administrative system), we would have expected full recognition of Sikhs as a distinct community in the British multicultural society after over 50 years of Sikh immigration. We are the largest single distinct minority (religio-ethnic) group in the United Kingdom, but we were not even recognized as such until 1983 (see below). Even today, that recognition has been less than forthcoming in areas such as monitoring of Sikhs as a distinct community with own religio-social identity, Sikh human rights, including religious rights and freedoms, and equal opportunities in various fields such as employment, education and representation at various levels of local and national government.

The media, which is also a part of British establishment, plays an important role in educating the public and changing set attitudes towards immigrant communities. In case of the Sikhs, it has, in fact, played quite the opposite role in creating confusion and distrust about Sikh identity. That despite the fact that the Sikhs are a hard working and law-abiding community least dependent on state benefits.

The ignorance which security agencies continue to show about Sikh identity in the UK and Europe is quite remarkable despite over 200 years of Anglo-Sikh relations.

Question of Sikh monitoring

Sikhs qualify under “ethnic”, “religious” or any other classification to be counted as a distinct community. Those who restrict Sikh counting to “religion” only, or prefer to wait for some possible future system which describes them more correctly, do not understand Sikh temporal-spiritual (miri-piri) tradition, or are just living in some unreal world while the community continues to suffer discrimination.

The Race Relations Act 1976 was meant to give equal rights to all ethnic minorities. However, the Sikhs were not protected by the Act, because they were not considered to be an ethnic group. It took seven years for the Sikhs to be given protection under the Race Relations law in 1983. In that year the House of Lords (in the case of Mandla v. Lee), ruled that the Sikhs qualified as an “ethnic” minority, albeit, by redefining “ethnicity” to some extent.

That did not please some individuals and the opportunity to be monitored under the current system as an ethnic minority was lost.

The unfortunate Sikh experience is that sometimes, personally held views are passed on as representative views of the UK Sikhs. One example in the context of the “ethnic” monitoring debate is that Sikhs are only a “religion” and not an ethnic community as defined by the House of Lords in the Mandla case. That is not a generally held view about Sikhi, which is a twin track spiritual-temporal way of life (the “miri-piri” approach).

The “ethnic” aspect is derived from an inseparable combination of many factors, which not only include an independent religious ideology but also, as one “people”, common heritage, history, language and culture. All those who become Sikhs, regardless of their previous background, automatically share these traits according to the Law Lords. Sikhi is a way of life which is now protected under the Race Relations legislation. Never mind what one’s personal views may be, that is the law of this land and Sikhs legally qualify for monitoring under any system based on “ethnicity” or “religion” or any other distinct theo-social community definition. Yet, there are some leading Sikh “lights” who continue to insist that we should continue to suffer disadvantages by not being counted and monitored unless it is on the basis of “religion” only.

UK Sikhs hope that a change in the monitoring system in future would give them the right to be monitored as a distinct community. Sikh Council UK can ensure that the collective views of the Sikhs are heard.

Government consultation preferences

Government departments prefer to consult Sikhs and, presumably, other communities, through established personal contacts only. Officials are usually reluctant to come to terms with changing circumstances and to meet new faces.

It is for Sikh organisations to present a united view when consulted by the government, departments and agencies. Communication experts should serve organisations to present that agreed view.

After the terrorist attack in America on 11th September, 2001, we also suffered due to mistaken identity, and misleading terrorist profiling of Sikhs by security agencies. Sikhs were attacked but the police did not keep figures because Sikhs are not monitored under the current system for collating statistics, despite the fact that in law (by virtue of the Mandla case 1983) Sikhs qualified under religious as well as ethnic categories.

Government consultation with the Sikhs has remained ineffective. Except for one recent selection in the Lords, visible Sikh identity is missing in the House of Commons. As a consequence, the Sikhs are hardly able to make any prior contribution to the process of law making to ensure that their religious identity and rights as a distinct community, are safeguarded. There is much frustration in the community. Either Sikhs have not been consulted before policy decisions about future legislation, or there have been misunderstandings that have led to a lack of protection of Sikh religious rights. Sometimes, the Government says that it has consulted Sikh “leaders”. We are left wondering who these Sikh representatives are, who advise the government departments.

Immediately after 11th September, 2001, without consultation, Sikhs were told not to wear the “kirpan. A Home Office Minister wrote to the Sikhs that he had been advised that Sikhs could carry small wooden or plastic “kirpans”. For practising Sikhs that was a cruel joke! Sikhs do not know to this day who gave that advice.

Before final summing up, there are some unique features of the Sikh way of life which should be noted. Compared with orthodox Semitic and eastern religious ideologies, the end purpose of Sikhi is to serve creation (as the image of the Creator) here and now. No other reward is expected or sought in some hereafter existence. This direct “here and now” activism - miri aspect of Sikhi - which has claimed countless martyrdoms, is inherent in “Raj Karega Khalsa”, “Degh, Tegh, Fateh” and “halemi raj” ideals. These are not exclusive but inclusive concepts for the wellbeing of all humanity.

Sikhi is more than a traditional “religion” due to its stress on action based life for the good of all.

Conclusion

Over 700,000 British Sikhs make up the largest religious and “ethnic” UK minority. In the last national census, Sikhs were given an optional “Religion” box to tick. However, religion is NOT used for monitoring any discrimination so that policy changes can be made to ensure a more level playing field in future. Monitoring of Sikhs under any current system is the first priority for the Sikh Council UK and affiliated organisations. Most other issues relate to this main goal which remains to be achieved.

Challenges to Sikh identity (ideological and visible) must be faced through better education of non-Sikhs including UK and European governments, authorities and security agencies. The French Dastaar issue, airport Dastaar searches, ban on wearing visible Sikh Kakaars, the Kirpaan and the Kara are the main challenges.

Fair share of visible Sikh representation in British public life is the third priority. Again this issue is relevant to the question of Sikh monitoring in different fields. Sikhs are not getting their fair share of senior appointments, awards and honours for community work. (It may be that mainstream Sikh organisations are slow to send timely nominations.)

Sikhs lack regular contacts with the mainstream national media. They should be in the news more often, projecting a positive image. Sikhs need effective media management at local and national levels. Only youngish, well educated and presentable Sikhs can do this. Older “jathedar” types must understand this and nominate and promote youngish Sikhs for such roles.

Sikh human rights area in the Indian context is a controversial but important issue. It continues to divide UK Sikhs but it must be faced, albeit, with presentational caution to ensure that British Sikhs are seen to be raising just concerns on humanitarian grounds. Like all UK citizens they have every right to do that through the Sikh Council UK and through the British government.

As mentioned at the outset, Sikh heritage including Anglo-Sikh heritage aspect, and global Sikhi seva in the field, are important for promoting Sikh identity but would be best left to voluntary organisations. Interpretation of Gurbani in the context of 21st Century issues is an ongoing need. Research by panels of UK Sikh scholars on some of these issues can be supported by organisations like the Sikh Missionary Society UK.

Ongoing discussion of priority issues and challenges which concern British Sikhs and the Sikh Council UK, is a learning process. Unhealthy official cronyism has been a divisive and damaging factor in British Sikh affairs. It is hoped that any criticism does not detract from the dedication and positive contribution of some individuals.

Diaspora Sikhs look up to British Sikhs to lead.

Gurmukh Singh UK

E-mail: sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright: Gurmukh Singh

Article may be published, or quoted from, with acknowledgment.

Due to the longstanding need felt by British Sikhs, the setting up of the Sikh Council UK has been widely welcomed. The Council has gained rapid recognition in government circles and is settling down to address the most important challenges we face today.

This is perhaps the right time to remind ourselves what the main issues and challenges are.

Internal divisions centred around personalities have been a major setback for Sikh unity and progress of Sikh issues. Effective communication at local and national levels in English has been the other difficulty. Without balanced presentation of Sikh problems to the government and departments in the language of the British establishment, Sikh jathebandis are unable to influence government policy.

In the past, some ambitious individuals have used the language difficulty to pursue own agendas. The influence they have on Sikh affairs has been far in excess of their knowledge of Sikh tradition or actual support at grassroots level. For example, the French Sikh turban case could have been handled much more openly and effectively from the start. However, personal ambition rather than knowledge of Sikh religious significance of dastaar, took over. In an attempt to seek exemption from French restrictions, by some clever argument, Sikh dastaar was presented as a “cultural” item instead of an essential religious requirement. Regrettably, as in other such cases, history is being re-written to gloss over such errors. In this case, other organisations were blamed for Sikh failure.

Despite some achievements, UK and European acceptance of Sikh identity has been incremental, and grudgingly conceded after much lobbying, demonstrations and legal battles. Due to lack of co-ordinated professional team-working at frontline level, progress made on the most important issues has been limited.

At individual level Sikhs are prosperous. Next generations are doing well in education and professions. However, despite being a sizeable community, Sikh identity is hardly seen in public life, politics and the Parliament. There is much ignorance about who Sikhs are. Future Sikh generations need to be proud of the “Sikh” part of their “Sikh British” identity to grow up as responsible citizens fully aware of own heritage and culture. Sense of belonging to a community is an important aspect of personal development and identity.

That sense of pride and belonging also depends on the acceptance of the community’s identity within the larger British plural society. That is one important goal for the Sikh Council UK.

Past achievements: Setting the record straight

Those who claim that they have been able to get results only through personal contacts are out of touch with ground realities. Despite exaggerated claims of individual contribution, success in the Mandla case, for example, was due to united support by the Sangat. The case reached the House of Lords and is regarded as a milestone achievement.

To set the record straight, I am content to quote S. Sewa Singh Mandla. In response to a query to clarify how the case was won, he wrote on 17 May 2010:

“A couple of years ago the Sikh Police Association London at their AGM wanted to celebrate 25th anniversary of Mandla v Lee case and had invited me to give a talk on the case and make a presentation, which I did. In my talk I said that having lost the case in the lower courts I realized that this case will affect the entire Sikh Community and as such I wanted to involve the Community in the case. With this in mind I went to Sant Baba Puran Singh Ji the Founder of Nishkam Sewak Jatha Birmingham (GNNSJ) and sought His Blessing and assistance.

It was GNNSJ who prepared information packs about Sikhism and the importance of the Turban to the Sikhs and send them out to all Members of Parliament and other important people to increase awareness and support. GNNSJ got support from all communities for this cause. It was GNNSJ which took a lead in the campaign and organized a mass rally at e Hyde Park in London . I showed the clip of the BBC Television interview with Sant Baba Puran Singh Ji, Bhai Sahib Norang Singh ji (the then Chairman of GNNSJ), Mr. Mavi of (CRE) and my self and I finally said that the case in the House of Lords was won purely with the Blessings of Sant Baba Puran Singh Ji. Now that is the truth. I know that it was GNNSJ who mobilised the entire community and in fact hired 70 coaches and send them to the Gurudwaras and other organisations who wanted to attend the rally at the Hyde Park.” (S. Sewa Singh Mandla’s e-mail of 17 May 2010)

Yet, this collective historic achievement is being re-written with a bias towards individual contribution to the ultimate success. The opportunity to build on a milestone victory for Sikh unity and identity, has been lost

The historical fact is that past achievements were due to united effort by Sikh Sangats. There are important lessons to be learnt. Ambitious activists with language and communication skills, otherwise dedicated to Panthic work, tend to take personal credit far in excess of their actual contribution. Their proximity with departmental officials gives them own following in the community. That is not in the community’s long term interest. Individuals with language skills should serve jathebandis; it is not for jathebandis to serve their personal aspirations.

Issues for the Sikh Council UK

The establishment of the Sikh Council UK gives us an opportunity to review the most important issues which concern us as a distinct religio-social community; the extent to which progress has been made and the challenges which we continue to face. These would be matters which need to be taken up by the Sikh Council and affiliated organisations, with the UK and European governments, agencies and authorities. Most other issues can be dealt with by Sikh organisations and Panthic jathebandis with experience in specific areas. Anglo-Sikh heritage, Khalsa Aid and legal representation of Sikh issues e.g. by United Sikhs, are important activities which promote Sikh identity, but need not be dealt with in the context of matters discussed under the umbrella of Sikh Council UK.

With regard to Sikh expectations from the British establishment (mainly the legislative/legal and administrative system), we would have expected full recognition of Sikhs as a distinct community in the British multicultural society after over 50 years of Sikh immigration. We are the largest single distinct minority (religio-ethnic) group in the United Kingdom, but we were not even recognized as such until 1983 (see below). Even today, that recognition has been less than forthcoming in areas such as monitoring of Sikhs as a distinct community with own religio-social identity, Sikh human rights, including religious rights and freedoms, and equal opportunities in various fields such as employment, education and representation at various levels of local and national government.

The media, which is also a part of British establishment, plays an important role in educating the public and changing set attitudes towards immigrant communities. In case of the Sikhs, it has, in fact, played quite the opposite role in creating confusion and distrust about Sikh identity. That despite the fact that the Sikhs are a hard working and law-abiding community least dependent on state benefits.

The ignorance which security agencies continue to show about Sikh identity in the UK and Europe is quite remarkable despite over 200 years of Anglo-Sikh relations.

Question of Sikh monitoring

Sikhs qualify under “ethnic”, “religious” or any other classification to be counted as a distinct community. Those who restrict Sikh counting to “religion” only, or prefer to wait for some possible future system which describes them more correctly, do not understand Sikh temporal-spiritual (miri-piri) tradition, or are just living in some unreal world while the community continues to suffer discrimination.

The Race Relations Act 1976 was meant to give equal rights to all ethnic minorities. However, the Sikhs were not protected by the Act, because they were not considered to be an ethnic group. It took seven years for the Sikhs to be given protection under the Race Relations law in 1983. In that year the House of Lords (in the case of Mandla v. Lee), ruled that the Sikhs qualified as an “ethnic” minority, albeit, by redefining “ethnicity” to some extent.

That did not please some individuals and the opportunity to be monitored under the current system as an ethnic minority was lost.

The unfortunate Sikh experience is that sometimes, personally held views are passed on as representative views of the UK Sikhs. One example in the context of the “ethnic” monitoring debate is that Sikhs are only a “religion” and not an ethnic community as defined by the House of Lords in the Mandla case. That is not a generally held view about Sikhi, which is a twin track spiritual-temporal way of life (the “miri-piri” approach).

The “ethnic” aspect is derived from an inseparable combination of many factors, which not only include an independent religious ideology but also, as one “people”, common heritage, history, language and culture. All those who become Sikhs, regardless of their previous background, automatically share these traits according to the Law Lords. Sikhi is a way of life which is now protected under the Race Relations legislation. Never mind what one’s personal views may be, that is the law of this land and Sikhs legally qualify for monitoring under any system based on “ethnicity” or “religion” or any other distinct theo-social community definition. Yet, there are some leading Sikh “lights” who continue to insist that we should continue to suffer disadvantages by not being counted and monitored unless it is on the basis of “religion” only.

UK Sikhs hope that a change in the monitoring system in future would give them the right to be monitored as a distinct community. Sikh Council UK can ensure that the collective views of the Sikhs are heard.

Government consultation preferences

Government departments prefer to consult Sikhs and, presumably, other communities, through established personal contacts only. Officials are usually reluctant to come to terms with changing circumstances and to meet new faces.

It is for Sikh organisations to present a united view when consulted by the government, departments and agencies. Communication experts should serve organisations to present that agreed view.

After the terrorist attack in America on 11th September, 2001, we also suffered due to mistaken identity, and misleading terrorist profiling of Sikhs by security agencies. Sikhs were attacked but the police did not keep figures because Sikhs are not monitored under the current system for collating statistics, despite the fact that in law (by virtue of the Mandla case 1983) Sikhs qualified under religious as well as ethnic categories.

Government consultation with the Sikhs has remained ineffective. Except for one recent selection in the Lords, visible Sikh identity is missing in the House of Commons. As a consequence, the Sikhs are hardly able to make any prior contribution to the process of law making to ensure that their religious identity and rights as a distinct community, are safeguarded. There is much frustration in the community. Either Sikhs have not been consulted before policy decisions about future legislation, or there have been misunderstandings that have led to a lack of protection of Sikh religious rights. Sometimes, the Government says that it has consulted Sikh “leaders”. We are left wondering who these Sikh representatives are, who advise the government departments.

Immediately after 11th September, 2001, without consultation, Sikhs were told not to wear the “kirpan. A Home Office Minister wrote to the Sikhs that he had been advised that Sikhs could carry small wooden or plastic “kirpans”. For practising Sikhs that was a cruel joke! Sikhs do not know to this day who gave that advice.

Before final summing up, there are some unique features of the Sikh way of life which should be noted. Compared with orthodox Semitic and eastern religious ideologies, the end purpose of Sikhi is to serve creation (as the image of the Creator) here and now. No other reward is expected or sought in some hereafter existence. This direct “here and now” activism - miri aspect of Sikhi - which has claimed countless martyrdoms, is inherent in “Raj Karega Khalsa”, “Degh, Tegh, Fateh” and “halemi raj” ideals. These are not exclusive but inclusive concepts for the wellbeing of all humanity.

Sikhi is more than a traditional “religion” due to its stress on action based life for the good of all.

Conclusion

Over 700,000 British Sikhs make up the largest religious and “ethnic” UK minority. In the last national census, Sikhs were given an optional “Religion” box to tick. However, religion is NOT used for monitoring any discrimination so that policy changes can be made to ensure a more level playing field in future. Monitoring of Sikhs under any current system is the first priority for the Sikh Council UK and affiliated organisations. Most other issues relate to this main goal which remains to be achieved.

Challenges to Sikh identity (ideological and visible) must be faced through better education of non-Sikhs including UK and European governments, authorities and security agencies. The French Dastaar issue, airport Dastaar searches, ban on wearing visible Sikh Kakaars, the Kirpaan and the Kara are the main challenges.

Fair share of visible Sikh representation in British public life is the third priority. Again this issue is relevant to the question of Sikh monitoring in different fields. Sikhs are not getting their fair share of senior appointments, awards and honours for community work. (It may be that mainstream Sikh organisations are slow to send timely nominations.)

Sikhs lack regular contacts with the mainstream national media. They should be in the news more often, projecting a positive image. Sikhs need effective media management at local and national levels. Only youngish, well educated and presentable Sikhs can do this. Older “jathedar” types must understand this and nominate and promote youngish Sikhs for such roles.

Sikh human rights area in the Indian context is a controversial but important issue. It continues to divide UK Sikhs but it must be faced, albeit, with presentational caution to ensure that British Sikhs are seen to be raising just concerns on humanitarian grounds. Like all UK citizens they have every right to do that through the Sikh Council UK and through the British government.

As mentioned at the outset, Sikh heritage including Anglo-Sikh heritage aspect, and global Sikhi seva in the field, are important for promoting Sikh identity but would be best left to voluntary organisations. Interpretation of Gurbani in the context of 21st Century issues is an ongoing need. Research by panels of UK Sikh scholars on some of these issues can be supported by organisations like the Sikh Missionary Society UK.

Ongoing discussion of priority issues and challenges which concern British Sikhs and the Sikh Council UK, is a learning process. Unhealthy official cronyism has been a divisive and damaging factor in British Sikh affairs. It is hoped that any criticism does not detract from the dedication and positive contribution of some individuals.

Diaspora Sikhs look up to British Sikhs to lead.

Gurmukh Singh UK

E-mail: sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright: Gurmukh Singh

Article may be published, or quoted from, with acknowledgment.

Tuesday, 13 December 2011

Sikh-Muslim Similarities & Question of Mistaken Identity

In the first week of December 2011, a Sikh preacher was stabbed by a 26-years old American at Fresno airport. Most probably, he was attacked because he looked like the turban-wearing bearded Islamic jihadis (religious warriors) who are fighting the Americans at places like Afghanistan. Bodies of dead American soldiers are arriving daily from that part of the world.

As other similar assaults on turban wearing Sikhs since 9/11, this life threatening attack too was probably due to mistaken identity.

A turban wearing bearded person is seen as a threat to security, even by ignorant or misguided officials in Western countries. Practising Sikhs are put on the defensive while real terrorists get away, literally, with murder !

At about the same time as the Fresno airport attack on the UK based Sikh preacher, a heated debate was going on under the heading, “Seeking Sikh Muslim Peace” on a cyber forum, Gurmat Learning Zone (GLZ). I started taking an interest when a Sikh writer, Nanak Singh Nishter, introduced his paper to the debate. He wrote, “To add further, following is my paper "Similarities between Muslims and Sikhs" to be submitted at a scheduled international seminar on "Islamic Culture & Art" being organised by the Maulana Azad National Urdu University at Hyderabad.”

In this paper, he writes, “There are seven Muslim co-authors of Shri Guru Granth Sahib.”

To describe the galaxy of bhagats honoured in Guru Granth Sahib, as co-authors of Guru Granth Sahib, is misleading. We also need to bear in mind that these saints associated with the God-loving bhagti movement, which preached One Divine Light in all, were socio-religious reformers of their time. They were often punished for their egalitarian teachings by the orthodox religions they were associated with by their birth. It may even be argued that they had opted out of the dogma based divisive ideologies of the orthodox religions.

It is necessary to quote one part of Nanak Singh Nishter’s paper at length, to show the extent to which our scholars bend over backwards to please Muslim audiences. He writes:

Quote starts:

"To elaborate the subject of the paper, I will confine to one very interesting fact worth mentioning found in an Urdu book “Muslims’ loving opinion about the Sikh Nation and their Founders” written by a Muslim luminary divine Hazrat Khaja Hasan Nizami. It is found in Khuda Bakhash Library, Patna, Bihar and was published on 27th December 1922 by the Khaja Press, Batala, Punjab. On page 8, under the subheading “Sikhs are Muslims”, he says, “Though politically Congress and the Government have accepted the special and separate existence of the Sikhs, but according to religious traditions, they are absolute Muslims. And the days are not far away when the Sikhs and Muslims will religiously unite”.

On page 10, he [Nizami] has scholarly proved the similarities of staunch belief in Formless Absolute One God, saying that there is “Bal brabar ka bhi faraq nahi hai” that is there is no difference not even as minute as hair. He has discussed at length the similarities between Sikhs and Muslims of faith, traditions, worships, so on and so forth in a very convincing manner. Further he has also projected the strange contradictions between Sikhs and Hindus, which do not compromise at any level.

On page 12, he [Nizami] says, “Summarising, there are hundreds of things which are common between them and the Muslims which shows that the Sikhs are Muslims and Muslims are Sikhs. Now it is the time for them that they should forget the previous political quarrels and become the two arms of Hindustan and lead their life”. Nobody can deny the fact that Sikhism and Islam are the most monotheistic religions and do not tolerate sharing of Absolute God with any other form." (Quote ends)

So, those are the views of Hazrat Nizami, quoted by Nanak Singh Nishter, apparently with approval, in a paper to be submitted at a scheduled international seminar.

Using all sorts of arguments to show how close Sikhi and Islam are, Nanak Singh Nishter also goes on to list gurdwaras named after Muslims. The average reader is left wondering, if a Sikh “scholar”, after much research is making those sort of admissions before an international audience at an Islamic university dominated by Islamic scholars, then the white American rednecks can be forgiven for thinking that Sikhs are Muslims!

I do hope our scholars and, especially those in the interfaith area, would wake up before it is too late. Sikh thought cannot be reconciled with any belief system of the dark ages. Any apparent similarities between New Age Sikh thought, and orthodox ideologies, hide some fundamental differences. For example, both, Sikhi and Islam preach One God, yet the "Ik Oangkaar" of Guru Nanak Sahib cannot possibly be reconciled with the Allah of Islam, who is given almost human attributes, and who sits outside creation (e.g. according to Dr Zakir Naik). Both religions preach acquisition of knowledge, yet Islamic "knowledge" must not go further than the dogma of Islam. One has to just watch “Peace TV” run by Dr Zakir Naik to fully understand that Islamic ideas of "peace" and “acquisition of knowledge” are conditional and very Islamic !

The myth that Guru Nanak Sahib agreed with the underlying teachings of all religions, has been exploded by great Sikh scholars like Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha and Professor Sahib Singh by using Gurbani grammer (e.g. the significance of different spellings of similar sounding words i.e. “laga(n) matra(n) de bhed”) and by interpreting Gurbani in the light of a holistic view of the teachings of Guru Granth Sahib. The Snatan dharmi misinterpretation of Gurbani has been totally rejected. The folk lore, idiom and allegory have been distinguished from the Guru’s own teaching of an independent life affirming Sikhi model.

The Guru’s own description of a true Muslim, and a true pundit/Brahmin etc is another way of rejecting these religions as interpreted by the followers and as practised. Guru ji’s advice to Muslims that they should be compassionate (Musalmaan momdil hovai) is another way of pointing out that, in practice, that is one quality missing in those who practise this ideology.

Muslim rulers were being exhorted by Muslim religious leaders to be cruel to their non-Muslim subjects. For example, the death punishment handed out to a Hindu youth Yodhan (in original Persian script also mentioned as Bodhan) by the Nawab of Lahore (about 1500 CE) was following a seminar of most Muslim religious scholars of northern India. This case is well documented by respected scholar Harbans Singh Noor in his book, “Connecting the dots in Sikh history.” All the youth had said was something to the effect that both, Islam and Hinduism are equally good religions. He was reported all the way to the Muslim ruler of Lahore who invited top Muslim religious scholars of Northern India to pronounce judgement, which was "either convert to Islam or die !"

There is no doubt that those who pronounced the death sentence for Yodhan were practising Muslims well versed in the teachings of Islam. It is possible that Guru Nanak Sahib at the age of 30 at the time, was much touched by this well reported case. Therefore, his cryptic response, "Na ko Hindu, na Musalmaan" i.e. there is no Hindu, and no Muslim, interpreted variously by scholars, depending upon own inclination!

Some say, giving examples from Sikh history, that not all Muslims are bad Muslims, but then not all Muslims are practising Muslims either ! It is for Islamic scholars and highest Islamic authorities to announce to the whole world the answer to the question, "Who is a good Muslim." The Sikhs should do the same. Only then can real similarities be agreed !

In Gurbani, there is no conscious attempt to reconcile or accept parts of orthodox ideologies. These are often quoted and rejected, to bring out the universal egalitarian values of Sikh thought.

Some years ago, during one local presentation before a multifaith audience, I did say light-heartedly, that given the choice, I would prefer to be beaten up in my own identity-right as a "Sikh" than as a "Masleem" by some ignorant hoodlum. I hope my Muslim brothers share the same sentiments. In fact, once in a while they should speak out against the Sikhs for not educating the ignorantia at large about their true Sikh identity; for, getting beaten up as “Muslims” is the well earned religious right of the Muslims !

As taught by the Guru, Sikhs see human race as one, while accepting and defending its rich diversity. There are many religions and schools of thought. The path of Sikhi too is distinct (niari). Nevertheless, when the Guru sees all human race as one and prays before Waheguru for the wellbeing of all and to save them no matter which religious path they follow, that does not mean that the Guru or his Sikhs agree with all that is taught or practised by those religions and cults. When we say that we should respect and preserve all life, that does not mean that we should respect the biting habit of a poisonous snake. We need to think carefully when we say “Sikhs respect all religions”. We need to reflect deeply about the shaheedi (martyrdom) of Guru Tegh Bahadur. Was it to save Hinduism, or was it for a Sikhi human rights principle ?

When the Islamic jihadi warrior (invader and marauder) and the Khalsa warrior (defender and protector), faced each other in the plains of 18th Century Panjab, both may have looked alike but they carried the inner conviction of two diametrically opposed ideologies. We suffer from the same mistaken identity today. Let us not make matters worse by accepting Sikh/Islamic similarities at interfaith forums, without in-depth research.

Dozens of well funded Islamic TV channels in the UK, run to the highest professional standards, are brainwashing millions in the name of Islam & peace on earth.

Orthodox religions have a long way to go to show the world that they really mean peace on earth. Regrettably, they cannot do this without dismantling much of the myth and dogma - the main pillars of their ideologies. Their aggressive form of evangelism is causing much interfaith friction.

The danger is that today's Sikhi(sm) and its highest institutions under Biparwaadi control, are weakening the reformation/revolutionary movement started by Guru Nanak Sahib to prepare human society for the New Age of science and discovery.

Sikh scholars should not feel apologetic for the independent path of Sikhi; nor can interfaith peace be based on doubtful similarities derived through tortuous interpretation of Sikh ideology and tradition.

(For further reading click www.sikhmissionarysociety.org – go to “publications”, “multifaith” and click “Sikh Religion & Islam”

Also related topic: “Sikh Approach to War & Peace”, Arches Quarterly, Vol 3 Edition 5 Dec 2009 - Feb 2010 ISSN 1756-7335 War, Peace & Reconciliation Cordoba Foundation - Cultures in Dialogue. www.the cordobafoundation.com

The article can be read

http://sewauk.blogspot.com/2010/05/sikhi-approach-to-war-peace.html

Gurmukh Singh UK

E-mail: sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright: Gurmukh Singh

Article may be published, or quoted from, with acknowledgment.

As other similar assaults on turban wearing Sikhs since 9/11, this life threatening attack too was probably due to mistaken identity.

A turban wearing bearded person is seen as a threat to security, even by ignorant or misguided officials in Western countries. Practising Sikhs are put on the defensive while real terrorists get away, literally, with murder !

At about the same time as the Fresno airport attack on the UK based Sikh preacher, a heated debate was going on under the heading, “Seeking Sikh Muslim Peace” on a cyber forum, Gurmat Learning Zone (GLZ). I started taking an interest when a Sikh writer, Nanak Singh Nishter, introduced his paper to the debate. He wrote, “To add further, following is my paper "Similarities between Muslims and Sikhs" to be submitted at a scheduled international seminar on "Islamic Culture & Art" being organised by the Maulana Azad National Urdu University at Hyderabad.”

In this paper, he writes, “There are seven Muslim co-authors of Shri Guru Granth Sahib.”

To describe the galaxy of bhagats honoured in Guru Granth Sahib, as co-authors of Guru Granth Sahib, is misleading. We also need to bear in mind that these saints associated with the God-loving bhagti movement, which preached One Divine Light in all, were socio-religious reformers of their time. They were often punished for their egalitarian teachings by the orthodox religions they were associated with by their birth. It may even be argued that they had opted out of the dogma based divisive ideologies of the orthodox religions.

It is necessary to quote one part of Nanak Singh Nishter’s paper at length, to show the extent to which our scholars bend over backwards to please Muslim audiences. He writes:

Quote starts:

"To elaborate the subject of the paper, I will confine to one very interesting fact worth mentioning found in an Urdu book “Muslims’ loving opinion about the Sikh Nation and their Founders” written by a Muslim luminary divine Hazrat Khaja Hasan Nizami. It is found in Khuda Bakhash Library, Patna, Bihar and was published on 27th December 1922 by the Khaja Press, Batala, Punjab. On page 8, under the subheading “Sikhs are Muslims”, he says, “Though politically Congress and the Government have accepted the special and separate existence of the Sikhs, but according to religious traditions, they are absolute Muslims. And the days are not far away when the Sikhs and Muslims will religiously unite”.

On page 10, he [Nizami] has scholarly proved the similarities of staunch belief in Formless Absolute One God, saying that there is “Bal brabar ka bhi faraq nahi hai” that is there is no difference not even as minute as hair. He has discussed at length the similarities between Sikhs and Muslims of faith, traditions, worships, so on and so forth in a very convincing manner. Further he has also projected the strange contradictions between Sikhs and Hindus, which do not compromise at any level.

On page 12, he [Nizami] says, “Summarising, there are hundreds of things which are common between them and the Muslims which shows that the Sikhs are Muslims and Muslims are Sikhs. Now it is the time for them that they should forget the previous political quarrels and become the two arms of Hindustan and lead their life”. Nobody can deny the fact that Sikhism and Islam are the most monotheistic religions and do not tolerate sharing of Absolute God with any other form." (Quote ends)

So, those are the views of Hazrat Nizami, quoted by Nanak Singh Nishter, apparently with approval, in a paper to be submitted at a scheduled international seminar.

Using all sorts of arguments to show how close Sikhi and Islam are, Nanak Singh Nishter also goes on to list gurdwaras named after Muslims. The average reader is left wondering, if a Sikh “scholar”, after much research is making those sort of admissions before an international audience at an Islamic university dominated by Islamic scholars, then the white American rednecks can be forgiven for thinking that Sikhs are Muslims!

I do hope our scholars and, especially those in the interfaith area, would wake up before it is too late. Sikh thought cannot be reconciled with any belief system of the dark ages. Any apparent similarities between New Age Sikh thought, and orthodox ideologies, hide some fundamental differences. For example, both, Sikhi and Islam preach One God, yet the "Ik Oangkaar" of Guru Nanak Sahib cannot possibly be reconciled with the Allah of Islam, who is given almost human attributes, and who sits outside creation (e.g. according to Dr Zakir Naik). Both religions preach acquisition of knowledge, yet Islamic "knowledge" must not go further than the dogma of Islam. One has to just watch “Peace TV” run by Dr Zakir Naik to fully understand that Islamic ideas of "peace" and “acquisition of knowledge” are conditional and very Islamic !

The myth that Guru Nanak Sahib agreed with the underlying teachings of all religions, has been exploded by great Sikh scholars like Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha and Professor Sahib Singh by using Gurbani grammer (e.g. the significance of different spellings of similar sounding words i.e. “laga(n) matra(n) de bhed”) and by interpreting Gurbani in the light of a holistic view of the teachings of Guru Granth Sahib. The Snatan dharmi misinterpretation of Gurbani has been totally rejected. The folk lore, idiom and allegory have been distinguished from the Guru’s own teaching of an independent life affirming Sikhi model.

The Guru’s own description of a true Muslim, and a true pundit/Brahmin etc is another way of rejecting these religions as interpreted by the followers and as practised. Guru ji’s advice to Muslims that they should be compassionate (Musalmaan momdil hovai) is another way of pointing out that, in practice, that is one quality missing in those who practise this ideology.

Muslim rulers were being exhorted by Muslim religious leaders to be cruel to their non-Muslim subjects. For example, the death punishment handed out to a Hindu youth Yodhan (in original Persian script also mentioned as Bodhan) by the Nawab of Lahore (about 1500 CE) was following a seminar of most Muslim religious scholars of northern India. This case is well documented by respected scholar Harbans Singh Noor in his book, “Connecting the dots in Sikh history.” All the youth had said was something to the effect that both, Islam and Hinduism are equally good religions. He was reported all the way to the Muslim ruler of Lahore who invited top Muslim religious scholars of Northern India to pronounce judgement, which was "either convert to Islam or die !"

There is no doubt that those who pronounced the death sentence for Yodhan were practising Muslims well versed in the teachings of Islam. It is possible that Guru Nanak Sahib at the age of 30 at the time, was much touched by this well reported case. Therefore, his cryptic response, "Na ko Hindu, na Musalmaan" i.e. there is no Hindu, and no Muslim, interpreted variously by scholars, depending upon own inclination!

Some say, giving examples from Sikh history, that not all Muslims are bad Muslims, but then not all Muslims are practising Muslims either ! It is for Islamic scholars and highest Islamic authorities to announce to the whole world the answer to the question, "Who is a good Muslim." The Sikhs should do the same. Only then can real similarities be agreed !

In Gurbani, there is no conscious attempt to reconcile or accept parts of orthodox ideologies. These are often quoted and rejected, to bring out the universal egalitarian values of Sikh thought.

Some years ago, during one local presentation before a multifaith audience, I did say light-heartedly, that given the choice, I would prefer to be beaten up in my own identity-right as a "Sikh" than as a "Masleem" by some ignorant hoodlum. I hope my Muslim brothers share the same sentiments. In fact, once in a while they should speak out against the Sikhs for not educating the ignorantia at large about their true Sikh identity; for, getting beaten up as “Muslims” is the well earned religious right of the Muslims !

As taught by the Guru, Sikhs see human race as one, while accepting and defending its rich diversity. There are many religions and schools of thought. The path of Sikhi too is distinct (niari). Nevertheless, when the Guru sees all human race as one and prays before Waheguru for the wellbeing of all and to save them no matter which religious path they follow, that does not mean that the Guru or his Sikhs agree with all that is taught or practised by those religions and cults. When we say that we should respect and preserve all life, that does not mean that we should respect the biting habit of a poisonous snake. We need to think carefully when we say “Sikhs respect all religions”. We need to reflect deeply about the shaheedi (martyrdom) of Guru Tegh Bahadur. Was it to save Hinduism, or was it for a Sikhi human rights principle ?

When the Islamic jihadi warrior (invader and marauder) and the Khalsa warrior (defender and protector), faced each other in the plains of 18th Century Panjab, both may have looked alike but they carried the inner conviction of two diametrically opposed ideologies. We suffer from the same mistaken identity today. Let us not make matters worse by accepting Sikh/Islamic similarities at interfaith forums, without in-depth research.

Dozens of well funded Islamic TV channels in the UK, run to the highest professional standards, are brainwashing millions in the name of Islam & peace on earth.

Orthodox religions have a long way to go to show the world that they really mean peace on earth. Regrettably, they cannot do this without dismantling much of the myth and dogma - the main pillars of their ideologies. Their aggressive form of evangelism is causing much interfaith friction.

The danger is that today's Sikhi(sm) and its highest institutions under Biparwaadi control, are weakening the reformation/revolutionary movement started by Guru Nanak Sahib to prepare human society for the New Age of science and discovery.

Sikh scholars should not feel apologetic for the independent path of Sikhi; nor can interfaith peace be based on doubtful similarities derived through tortuous interpretation of Sikh ideology and tradition.

(For further reading click www.sikhmissionarysociety.org – go to “publications”, “multifaith” and click “Sikh Religion & Islam”

Also related topic: “Sikh Approach to War & Peace”, Arches Quarterly, Vol 3 Edition 5 Dec 2009 - Feb 2010 ISSN 1756-7335 War, Peace & Reconciliation Cordoba Foundation - Cultures in Dialogue. www.the cordobafoundation.com

The article can be read

http://sewauk.blogspot.com/2010/05/sikhi-approach-to-war-peace.html

Gurmukh Singh UK

E-mail: sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright: Gurmukh Singh

Article may be published, or quoted from, with acknowledgment.

Friday, 5 August 2011

Evolution of Indian & Sikh Classical Raag Tradition

(Note: Punjabi word meanings becomes clearer as you read on. Published by Sikhnet.)

There is a mistaken belief amongst Gurbani Keertan purists sometimes that Indian and Sikh classical raag have remained static over the centuries. Gurbani singers like Sikh “world music” genre pioneer, Dya Singh of Australia, are at the receiving end of criticism because they do not always stick to the beaten track of traditional Gurbani Keertan sung to prescribed raag bases.

Dya Singh’s distinctly Sikh “world music” (fusion music) mission and a milestone achievement in his forthcoming Gurbani album release “Dukh bhanjan Tera Naam” is discussed in the previous article. In that context, this item summarises the evolution of Indian and Sikh classical sangeet over the centuries to inform ongoing discussion under this thread.

Indian classical raag (raga)

Very few Indian raag (usage singular or plural - see below) have survived in their original form. In fact most Indian classical raag sung or played on musical instruments today, are a mixture of middle-eastern and ancient Indian music and were given their present form from the 13th century onwards. The name of Hazrat Amir Khusro, a courtier of Emperor Allaodin Khilji, is associated with the establishment of the Northern Indian School of music. The poet Lochan in the fifteenth century first introduced the concept of thaat (literally means “harmony” or “combination” in Sanskrit). A southern Indian scholar, Pandat Vayankatmukhi, worked out mathematically that it was possible to have 72 thaat but even he used only 19 of these to classify raag. Finally in the 19th century, a great scholar of music Pandit Vishnu Narain Bhaatkhande selected only 10 thaats based on 12 notes (7 shudh and 5 komal/thibar) to classify Indian raag. This is the system in use throughout India today, although, many music schools continue to disagree with this modern classification.

The ancient system of classifying raag into families i.e. main raag and their derivative “wives and sons” described in the “Ragmala” in Sri Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS), has not been used for many centuries since the introduction of thaat. Many scholars of Indian music regard this as a great sacrilege and corruption of the ancient raag (Shastri sangeet); others see the change to the current (comparatively) much simpler system as a vehicle for making Indian classical music more popular and accessible. This change would be in the spirit of Gurbani keertan or sangeet.

What is a raag

Without going into the technicalities , a raag should be capable of capturing and enhancing the mood:

- of the time e.g. morning or evening etc;

- the season e.g. spring, monsoon etc.; or,

- an emotion e.g. joy, sorrow, longing, bravery, patriotism, peace, detachment, spiritual fulfilment etc.

Some believe that raag are endowed with soothing, healing, spiritual and even miraculous powers. For example, it was believed that Raag Megh sung meditatively in its pure form, could bring rain and Deepak could light lamps. The rules of raag were well defined but have changed over the centuries. So much so that many different ghranas (houses or schools of raag ) have emerged with their own versions of raag. Yet, the classical Indian music ear and heart will know when a raag is played or sung by a maestro. The rules of Indian classical music based on western 12 keys were redefined by Pundit Vishnu Narain Bhaatkhande in the 19th century. Before that Indian raags were based on 7- key notes further divided into 22 shrutee and arranged to certain musical note combinations used by ancient rishi musicians. In Indian raag parlance these systems were based on shrutee and moorshna.

Many prominent masters disagreed, and continue to disagree, with this change from shrutee- based division of the present day octave (division of keys between one “sa” and the next higher on the musical scale). Pundit Firoz Fraam (of Poona) and Pundit Vinaik Narain Patvardhan were prominent amongst the leading opponents who claimed that there was strong middle-eastern music influence (backed by the ruling Mughal preferences) behind this change. The harmonium or the piano and similar modern fixed key instruments are not accepted as proper musical instruments by these purists. Indeed some classical raagis (raag singers) refer to the harmonium derisively as “peti” (box), an instrument of beggars, for it was mostly used by street beggars in Europe and the Middle-east. (I took some satisfaction by pointing this out to a member of a hajoori raagi jatha of Darbar Sahib, who derided the variety of string instruments (taanti saaj) played by Dya Singh’s companions.)

Such controversies will remain and will continue to grow as Indian classical tradition is exposed to world music and international influences; and as Indian musicians respond to the rhythm and beat appreciated by western and westernised ears. Increasing use of east-west musical instruments is a part of this trend. Dya Singh music has used the western piano, guitar and violin to great effect.

What is Gurbani Kirtan ?

Gurbani kirtan or sangeet, is the singing of Gurbani, the Word of the Guru, in accordance with raag- based guidance given in Sri Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS), the holy Scripture of the Sikhs. The aim of Gurbani Kirtan is to enhance the impact of the Guru’s Word (Gurbani or Shabad) on the human soul (atma) and to harmonise it with the Universal Soul (Param Atma) by achieving a state of bliss (anand).

Kirtan is a form of meditative music (bhagti sangeet). The development of bhagti sangeet in India dates back to the evolution of religious thought and gained momentum with the progress of the bhagti movement in India from about 11th Century C.E. onwards. There is a long list of the bhagats (saints with Hindu or Muslim backgrounds preaching universal love of God) like Tulsi Das, Meera, Jaidev, Namdev, Shaikh Farid, Ravidas, Kabir etc who promoted bhagti sangeet. The next phase of bhagti sangeet was introduced by the Sikh Gurus starting with Guru Nanak Sahib (1469 to 1539 A.D.) as Gurbani keertan.

In an ancient Indian scripture, the Lord says “Where my bhagats sing my praises there I reside.” The Sikh Gurbani confirms “Tahan baikunt jeh kirtan Tera” (“Heaven is where Your praise is sung.”) Gurbani sangeet started when Guru Nanak said to his musician companion Mardana “Touch the string of your rabaab (rebeck) O’ Mardana, I am receiving Bani (the Divine Word)”.

Guru Nanak composed and sang Gurbani in 19 classical raag; Guru Amardas (Third Guru) in 17, Guru Ramdas (Fourth Guru) in 29 and Guru Arjan Dev (Fifth Guru) in 30 raag. There are altogether 31 shudh (pure) raag in SGGS and many further raag combinations and popular folk tunes.

Guru Nanak travelled extensively. He sang to the people outdoors, sitting under the shade of trees or in the open fields. He sang in many different languages and popular tunes (vaars and dhunees). He went out there and communicated with the ordinary people using the language and music which they understood and loved. Yet, he preserved the essential character of classical raag tradition as well and selected raag bases to enhance the spiritual message of Gurbani, the Guru's Word.

It may be argued that Dya Singh too is following in his Guru’s footsteps by taking Gurbani to world audiences in the world-musical language they relate to.

The main criterion for the raag bases selected by the Gurus was that Gurbani singing should enhance the spiritual message of Gurbani and induce a mood of meditation and spiritual equipoise (sehaj anand).

Some facts about Gurbani raag bases, folk tunes, beats and rhythms are as follows:

a) There are 31 main raag in Guru Granth Sahib.

b) In addition there are almost as many mixed raag, popular folk music called dhunee (rhythm and beat) used. The different types of vaars (songs about heroes, wars and popular love stories) are examples of these popular tunes. Some examples are:

- Tunde Asraje ki dhunee

- Malik Mureed tatha Chandra Sohian ki dhunee

- Rai Kamal Maujdi ki vaar ki dhunee

- Jodhe Vire Purbani ki dhunee

- Rai Mehme Hasne ki dhunee

- Lalla Behlima ki dhunee

- Raaney Kailash tatha Maaldey ki dhunee

c) Popular folk tunes include ghorian, satta, bir-harey and alahonian.

d) Guru Gobind Singh Ji composed Gurbani (in Dasam Granth which includes compositions of Guru Gobind Singh and some other Sikh poets) in popular raags, folk tunes, rhythms and beats. It is said that Guru Ji was an accomplished musician in 235 raags. Indeed, Dasam Granth reputedly includes poetry to the beat of ferangi taal ! Many years ago, during a discussion, I was amazed to hear elderly and well known Sikh scholar and raagi, Giani Nahar Singh, giving an example by playing this disco type of drum beat on the arms of a wooden chair, while singing a few lines of a composition from Dasam Granth to that beat.

e) The Sikh dhadis to this day sing martial songs of Sikh heroes and even Gurbani Shabads to music bases of popular vars and love stories e.g. those of Mirza, Heer etc.

f) Guru Nanak Sahib's music companion was Bhai Mardana, a Muslim. Some popular raagis of Darbar Sahib and other major Gurdwaras e.g. Bhai Chaand at Darbar Sahib and Bhai Laal at Nankana Sahib have been Muslim (response to those who sometimes, in their ignorance, do not allow non-Sikh musician companions of Dya Singh on Gurdwara stages.) Yet, there are good reasons why Sikh Reht Maryada allows keertan in Sangat by Sikhs only. There is no mention of non-Sikh musicians on gurdwara stage. It is heartening to see on Sikh TV channels , recordings of classical raagi, elderly Bhai Balbir Singh doing Asa ki Vaar accompanied by Sikh and non-Sikh taanti saaj (string instrument) players on gurdwara stage.

With few exceptions, most Gurbani is in classical raag and should preferably be sung to those raag bases. However, as we have seen above, any rigid application of this rule would go against the underlying spirit of Gurbani sangeet.

Raag bases and instrumental skills are aids to the globalisation of Sarab Sanjhi Bani - Word received for the benefit of humankind - in many languages and musical traditions, which, as we have seen, continue to evolve. Let accomplished Gurbani sangeetkars follow in the footsteps of Guru Nanak Sahib and Bhai Mardana, and take the soothing and spiritual message of Gurbani to audiences worldwide.

Gurmukh Singh

Ret’d Principal (policy), UK Civil Service

E-mail: sewauk2005@yahoo.co.uk

Copyright: Gurmukh Singh

Article may be published or quoted from, with due acknowledgment.

Sources:

In addition to own inherited knowledge of Gurbani Keertan, the following publications in Punjabi have been my constant companions for many years:

Principal Dyal Singh: “Gurmat Sangeet Sagar” (4 Volumes) 1992, Guru Nanak Vidya Bhandaar Trust, New Delhi.

Sant Sarwan Singh Gandharv: “Sur Simran Sangeet” (7 Volumes) 1990, Purbi Printing Press, Jalandhar.

Bhai Sahibs Avtar Singh &; Gurcharan Singh “Gurbani Sangeet Praacheen Reet ratnaavli” (2 Volumes) 1979, Punjabi University, Patiala.

Of the above, books by Principal Dyal Singh are user friendly and recommended.

There is a mistaken belief amongst Gurbani Keertan purists sometimes that Indian and Sikh classical raag have remained static over the centuries. Gurbani singers like Sikh “world music” genre pioneer, Dya Singh of Australia, are at the receiving end of criticism because they do not always stick to the beaten track of traditional Gurbani Keertan sung to prescribed raag bases.

Dya Singh’s distinctly Sikh “world music” (fusion music) mission and a milestone achievement in his forthcoming Gurbani album release “Dukh bhanjan Tera Naam” is discussed in the previous article. In that context, this item summarises the evolution of Indian and Sikh classical sangeet over the centuries to inform ongoing discussion under this thread.

Indian classical raag (raga)

Very few Indian raag (usage singular or plural - see below) have survived in their original form. In fact most Indian classical raag sung or played on musical instruments today, are a mixture of middle-eastern and ancient Indian music and were given their present form from the 13th century onwards. The name of Hazrat Amir Khusro, a courtier of Emperor Allaodin Khilji, is associated with the establishment of the Northern Indian School of music. The poet Lochan in the fifteenth century first introduced the concept of thaat (literally means “harmony” or “combination” in Sanskrit). A southern Indian scholar, Pandat Vayankatmukhi, worked out mathematically that it was possible to have 72 thaat but even he used only 19 of these to classify raag. Finally in the 19th century, a great scholar of music Pandit Vishnu Narain Bhaatkhande selected only 10 thaats based on 12 notes (7 shudh and 5 komal/thibar) to classify Indian raag. This is the system in use throughout India today, although, many music schools continue to disagree with this modern classification.

The ancient system of classifying raag into families i.e. main raag and their derivative “wives and sons” described in the “Ragmala” in Sri Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS), has not been used for many centuries since the introduction of thaat. Many scholars of Indian music regard this as a great sacrilege and corruption of the ancient raag (Shastri sangeet); others see the change to the current (comparatively) much simpler system as a vehicle for making Indian classical music more popular and accessible. This change would be in the spirit of Gurbani keertan or sangeet.

What is a raag

Without going into the technicalities , a raag should be capable of capturing and enhancing the mood:

- of the time e.g. morning or evening etc;

- the season e.g. spring, monsoon etc.; or,

- an emotion e.g. joy, sorrow, longing, bravery, patriotism, peace, detachment, spiritual fulfilment etc.

Some believe that raag are endowed with soothing, healing, spiritual and even miraculous powers. For example, it was believed that Raag Megh sung meditatively in its pure form, could bring rain and Deepak could light lamps. The rules of raag were well defined but have changed over the centuries. So much so that many different ghranas (houses or schools of raag ) have emerged with their own versions of raag. Yet, the classical Indian music ear and heart will know when a raag is played or sung by a maestro. The rules of Indian classical music based on western 12 keys were redefined by Pundit Vishnu Narain Bhaatkhande in the 19th century. Before that Indian raags were based on 7- key notes further divided into 22 shrutee and arranged to certain musical note combinations used by ancient rishi musicians. In Indian raag parlance these systems were based on shrutee and moorshna.

Many prominent masters disagreed, and continue to disagree, with this change from shrutee- based division of the present day octave (division of keys between one “sa” and the next higher on the musical scale). Pundit Firoz Fraam (of Poona) and Pundit Vinaik Narain Patvardhan were prominent amongst the leading opponents who claimed that there was strong middle-eastern music influence (backed by the ruling Mughal preferences) behind this change. The harmonium or the piano and similar modern fixed key instruments are not accepted as proper musical instruments by these purists. Indeed some classical raagis (raag singers) refer to the harmonium derisively as “peti” (box), an instrument of beggars, for it was mostly used by street beggars in Europe and the Middle-east. (I took some satisfaction by pointing this out to a member of a hajoori raagi jatha of Darbar Sahib, who derided the variety of string instruments (taanti saaj) played by Dya Singh’s companions.)

Such controversies will remain and will continue to grow as Indian classical tradition is exposed to world music and international influences; and as Indian musicians respond to the rhythm and beat appreciated by western and westernised ears. Increasing use of east-west musical instruments is a part of this trend. Dya Singh music has used the western piano, guitar and violin to great effect.

What is Gurbani Kirtan ?

Gurbani kirtan or sangeet, is the singing of Gurbani, the Word of the Guru, in accordance with raag- based guidance given in Sri Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS), the holy Scripture of the Sikhs. The aim of Gurbani Kirtan is to enhance the impact of the Guru’s Word (Gurbani or Shabad) on the human soul (atma) and to harmonise it with the Universal Soul (Param Atma) by achieving a state of bliss (anand).

Kirtan is a form of meditative music (bhagti sangeet). The development of bhagti sangeet in India dates back to the evolution of religious thought and gained momentum with the progress of the bhagti movement in India from about 11th Century C.E. onwards. There is a long list of the bhagats (saints with Hindu or Muslim backgrounds preaching universal love of God) like Tulsi Das, Meera, Jaidev, Namdev, Shaikh Farid, Ravidas, Kabir etc who promoted bhagti sangeet. The next phase of bhagti sangeet was introduced by the Sikh Gurus starting with Guru Nanak Sahib (1469 to 1539 A.D.) as Gurbani keertan.

In an ancient Indian scripture, the Lord says “Where my bhagats sing my praises there I reside.” The Sikh Gurbani confirms “Tahan baikunt jeh kirtan Tera” (“Heaven is where Your praise is sung.”) Gurbani sangeet started when Guru Nanak said to his musician companion Mardana “Touch the string of your rabaab (rebeck) O’ Mardana, I am receiving Bani (the Divine Word)”.